More Q and A on Sentimental Jewelry

Kate asks:

Q: Is the jewellery we wear much more than a possession?

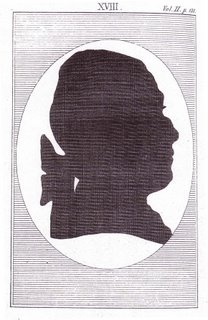

A: Yes, sentimental jewelry holds more emotional sway than other mere possessions. Sentimental jewelry are deeply personal jewels that record and memorialize emotion and important life events. This ability to carry emotional connections rests at the heart of sentimental jewelry, and artists and jewelers were well aware of this functional aspect of sentimental objects. For example, Charles Fraser, in his eulogy for fellow miniaturist Edward Greene Malbone, wrote, “He imparted such life to the ivory, and produced such striking resemblances, that they will never fail to perpetuate the tenderness of friendship, to divert the care of absence, and to aid affection in dwelling on those features and that image, which death has forever wrested in it.” Whether that sentiment was love, friendship, or mourning, sentimental jewelry spoke to the sensibility – an emotional consciousness and an acute apprehension of feeling – of its owner, and it synecdochically represented a loved one by incorporating fragments of the body (hair, eyes, mouth, hands, breasts, face, shadow, and even teeth) into the artifact. In this way, sentimental jewelry commoditized the human body and literally reified a human relationship.

Q: How has the meaning of sentiment changed over time within jewellery but also within our society? And why these changes have happened.

A: This is a really big question and one that I cover in more depth in my dissertation than the space of a blog allows, but I'll try to sketch an answer.

With the industrial revolution, changes in manufacturing yielded a change in material culture that in turn yielded a change in the pattern of consumption. Prior to the industrial revolution, artisans tended to manufacture small numbers of very expensive gem-encrusted items to meet the demands of the aristocracy for luxury goods. Portrait miniatures and eye miniatures painted with watercolor on thin ivory disks as well as larger portraits painted in oil on canvas are typical examples of artisan manufactured goods consumed by the landed aristocracy. Following the maturation of the industrial revolution, portrait and eye miniatures ceased to be produced. They were replaced by mass produced jewelry, especially mourning jewelry, and Daguerreotype photography. The reduced expense of these goods coupled with their wide availability allowed for middle class consumption of sentimental objects.

Where the aristocracy augmented their jewelry with hair, the bourgeoisie constructed jewelry almost entirely of hair. With this change can be discerned a change in class perception of body fragmentation that mirrors the changes in economic and productive re-organization of society. For the aristocracy, whose wealth was largely underwritten by agrarian capitalism or merchant capitalism, the fragmentation of the body corresponded to the fragmentation of the family and extended relationships, friends and lovers. Their jewelry functioned as the contemplative locus of pensive reverie, and the body fragment itself – the face in the portrait miniature, eye, and hair – synecdochically represented the separated loved one(s). For the urban bourgeoisie, extensive long-term travel did not dominate their lives. Their body fragmentation increasingly reflected a compartmentalization of perception, a disaggregated and mechanistic view of the body in science, medicine, industry, and discourse. The fragmentation of the family shifted from periodic absence to death, and mourning became an explosive new industry in the nineteenth century. Mourning attire, art, jewelry, stationary, photographic portraiture of the deceased, mourning ritual, and period of mourning became codified and standardized. Even the pin factory, Adam Smith’s classic example of industrial manufacturing, was not exempt from production for mourning. Mourning pins with black steel shafts and black glass heads were mass produced and were considered appropriate for mourning dress – a shiny steel pin would upset the somber gravity of the plain all black attire. All of this marks a dramatic change in the attitudes toward death and the practice of mourning in the eighteenth century.

Q: Do we now show our sentiment towards one another in a different way?

A: Yes and no. Sentimental jewelry of the type I write about really ceased to be produced much after the first world war. Instead, birth stones, mother's rings, and diamond engagement rings became standard ways of expressing relationships in the twentieth century. Though some may still keep a lock of their baby's hair or a lock from a dead parent, these relics by and large do not find their way into jewelry. Twentieth century jewelry of sentiment moved away from incorporating body fragments, which are now seen as largely macabre. However, I have become interested in the mourning memorials people place on the windshields of their cars, such as "In Memory of My Beloved Brother, John Doe, Jan. 1 1980 - Jan. 1 2005."

Q: Is the jewellery we wear much more than a possession?

A: Yes, sentimental jewelry holds more emotional sway than other mere possessions. Sentimental jewelry are deeply personal jewels that record and memorialize emotion and important life events. This ability to carry emotional connections rests at the heart of sentimental jewelry, and artists and jewelers were well aware of this functional aspect of sentimental objects. For example, Charles Fraser, in his eulogy for fellow miniaturist Edward Greene Malbone, wrote, “He imparted such life to the ivory, and produced such striking resemblances, that they will never fail to perpetuate the tenderness of friendship, to divert the care of absence, and to aid affection in dwelling on those features and that image, which death has forever wrested in it.” Whether that sentiment was love, friendship, or mourning, sentimental jewelry spoke to the sensibility – an emotional consciousness and an acute apprehension of feeling – of its owner, and it synecdochically represented a loved one by incorporating fragments of the body (hair, eyes, mouth, hands, breasts, face, shadow, and even teeth) into the artifact. In this way, sentimental jewelry commoditized the human body and literally reified a human relationship.

Q: How has the meaning of sentiment changed over time within jewellery but also within our society? And why these changes have happened.

A: This is a really big question and one that I cover in more depth in my dissertation than the space of a blog allows, but I'll try to sketch an answer.

With the industrial revolution, changes in manufacturing yielded a change in material culture that in turn yielded a change in the pattern of consumption. Prior to the industrial revolution, artisans tended to manufacture small numbers of very expensive gem-encrusted items to meet the demands of the aristocracy for luxury goods. Portrait miniatures and eye miniatures painted with watercolor on thin ivory disks as well as larger portraits painted in oil on canvas are typical examples of artisan manufactured goods consumed by the landed aristocracy. Following the maturation of the industrial revolution, portrait and eye miniatures ceased to be produced. They were replaced by mass produced jewelry, especially mourning jewelry, and Daguerreotype photography. The reduced expense of these goods coupled with their wide availability allowed for middle class consumption of sentimental objects.

Where the aristocracy augmented their jewelry with hair, the bourgeoisie constructed jewelry almost entirely of hair. With this change can be discerned a change in class perception of body fragmentation that mirrors the changes in economic and productive re-organization of society. For the aristocracy, whose wealth was largely underwritten by agrarian capitalism or merchant capitalism, the fragmentation of the body corresponded to the fragmentation of the family and extended relationships, friends and lovers. Their jewelry functioned as the contemplative locus of pensive reverie, and the body fragment itself – the face in the portrait miniature, eye, and hair – synecdochically represented the separated loved one(s). For the urban bourgeoisie, extensive long-term travel did not dominate their lives. Their body fragmentation increasingly reflected a compartmentalization of perception, a disaggregated and mechanistic view of the body in science, medicine, industry, and discourse. The fragmentation of the family shifted from periodic absence to death, and mourning became an explosive new industry in the nineteenth century. Mourning attire, art, jewelry, stationary, photographic portraiture of the deceased, mourning ritual, and period of mourning became codified and standardized. Even the pin factory, Adam Smith’s classic example of industrial manufacturing, was not exempt from production for mourning. Mourning pins with black steel shafts and black glass heads were mass produced and were considered appropriate for mourning dress – a shiny steel pin would upset the somber gravity of the plain all black attire. All of this marks a dramatic change in the attitudes toward death and the practice of mourning in the eighteenth century.

Q: Do we now show our sentiment towards one another in a different way?

A: Yes and no. Sentimental jewelry of the type I write about really ceased to be produced much after the first world war. Instead, birth stones, mother's rings, and diamond engagement rings became standard ways of expressing relationships in the twentieth century. Though some may still keep a lock of their baby's hair or a lock from a dead parent, these relics by and large do not find their way into jewelry. Twentieth century jewelry of sentiment moved away from incorporating body fragments, which are now seen as largely macabre. However, I have become interested in the mourning memorials people place on the windshields of their cars, such as "In Memory of My Beloved Brother, John Doe, Jan. 1 1980 - Jan. 1 2005."