Mourning Jewelry

"Whoever comes to shroud me, do not harm nor question much that subtle wreath of hair, which crowns my arm" - John Donne, The Funeral 1633

"Whoever comes to shroud me, do not harm nor question much that subtle wreath of hair, which crowns my arm" - John Donne, The Funeral 1633As Donne’s poem implies, both love tokens – the hairwork bracelet – and hair in funerary contexts – mourning jewelry – existed in Europe and America for some centuries. However, the social meanings ascribed to such jewelry and their precise role in grieving the deceased changed profoundly over that period. Mourning jewelry, as we are most likely to think of it today, exploded in the nineteenth century as industrial production brought “fashionable” mourning items within reach of the middle classes. With the expansion of capitalism, mourning ritual became codified, standardized, and regimented. Even the pin factory, Adam Smith’s classic example of industrial manufacturing, was not exempt from production for mourning! Mourning push pins with black glass heads and black steel shafts were considered most appropriate for the stark mourning attire.

This is one of my favorites; it was found in an old family bible. The mourning scene is composed entirely from human hair on milk glass. It contains all the standard elements: weeping willow, tomb, idyllic setting, flowers, and painted in the background sunset yellow, orange, and pink streak across the horizon.

Strand upon strand was layered to create a three dimensional effect and finely chopped hair added last to give the scene greater depth and scale. These three dimensional hairwork pieces are exceptionally rare, and this one probably dates to the mid nineteenth century.

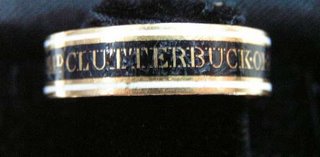

Mourning ring inscribed “EDMD. CLUTTERBUCK. OB: 8 DEC. 1797 IN HIS 77TH YEAR” in gold letters surrounded by black enamel and white enamel bands. Edmund Clutterbuck lived in Islington, Middlesex. He married Susannah Cappe on 20 Feb. 1757, and they had two daughters: Susannah born 4 Jan. 1758 and Sarah born 29 June 1761. Mrs. Clutterbuck died on 6 July 1761 probably from complications in giving birth to Sarah. Edmund married his second wife, Anne Goddard, on 24 Aug. 1766.

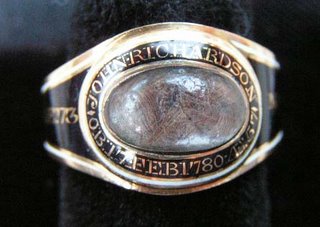

Mourning ring with hair under crystal and two inscriptions: “JOHN RICHARDSON. OB: 17 FEB. 1780 Æ: 57” and “MARGT. RICHARDSON. OB: 27 FEB. 1800 Æ: 73. Most likely John and Margaret Richardson of Cardington, Bedford. They had three children: Henry born 24 September 1752, William 16 March 1755 - 23 May 1756, and William 7 August 1757 - 28 September 1760.

After the Queen Mother died on 30 March 2002 Æ: 101, one pundit said something to the effect, “In her lifetime mourning, once a public act, became private, while sex, once a private act, became public.” There’s probably some truth to this. As mourning jewelry waned in the 1890s becoming virtually forgotten by the 1920s, pornographic visual culture continued to become more and more prevalent, and we may consider pornographic lockets as one waypoint in this social process.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home